Tacrolimus

Clinical History

The patient is a 14-year-old female status post cadaveric liver transplant 8 years ago for tyrosinemia. She has done well in her course except for some early complications with EBV infection and angioplasties for arterial thrombosis in the first 3 years. She has never had a rejection episode. Surprisingly, during some recent routine blood tests her liver enzymes were elevated. These results precipitated her admission for a liver biopsy.

The findings on liver biopsy and peripheral blood smear prompted her being seen by pediatric gastroenterology. The patient denied any symptoms whatsoever except for some mild head cold symptoms. She has had no problems with abdominal pain, dysphagia, or other GI symptoms. She has had no jaundice or weight loss. She did admit to loose stool when eating greasy or spicy food. She has no allergic symptoms.

Past Medical History

-

Tyrosinemia diagnosed at age 5. She had a brother who died at 3 months of age leading to her diagnosis of tyrosinemia. She also has an older brother who is not a homozygote for the disease.

-

Problems with calcium carbonate deposition in her kidneys.

-

Renal rickets when she was 3 years old.

-

EBV infection in the first year post transplant.

-

ADHD.

-

Fanconi’s Syndrome

Meds

-

Tacrolimus 1.5mg bid.

-

Celexa 20 mg qd.

-

Concerta 54 mg qd.

-

Chlorthalidone 25mg tid.

-

Aspirin 81mg qd.

Lab Data

|

Stool: |

No ova or parasites isolated. |

|

AST: |

227 U/L* |

|

ALT: |

407 U/L* |

|

Total Bilirubin: |

0.5 mg/dL |

|

Alkaline phosphatase: |

215 U/L |

|

Tacrolimus level: |

Has always hovered around 5 ng/mL, but did reach 8.6 ng/mL around the time of her biopsy. Her mom says that she has always been on the same dose and has always had good levels. |

|

RAST: |

Essentially negative; however, She did react to chocolate (726 kU/L originally, but dropped to <0.35 kU/L) and cat epithelium (50.9 kU/L, new reactivity) as well as weakly to wheat (1.09 kU/L) |

|

PT: |

14.5 sec |

|

INR: |

1.1 |

|

IgE: |

2093 IU/mL |

|

Peripheral Eosinophils: |

Began creeping up in December 1998 and has remained consistently high since then. Her percentage of eosinophils in her CBC usually resides around 10-20%. At the time of her biopsy she was at about 20.5%. She peaked a few weeks later at over 40%. They have since gone down. |

*The transaminases have since normalized.

Microscopic Examination

Click an image to view larger format.

Figure 1

Figure 2

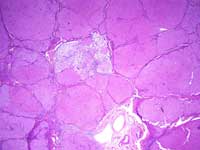

Figure 1: Native Chronic Tyrosinemia

-

Well-established cirrhosis.

-

Varying degrees of fatty change.

-

Glycogen-rich cytoplasm.

-

Cholestatic rosettes.

-

Scattered mononuclear inflammatory cells.

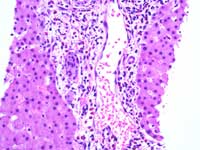

Figure 2: Transplant liver biopsy: Significant eosinophilia

-

Massive eosinophilic infiltrates in portal tract.

-

Portal edema.

-

Occasional eosinophils in sinusoids.

-

No fibrosis or steatosis.

-

Rejection activity index: 3/8.

Discussion

Several disorders of tyrosine metabolism have been identified, but only tyrosinemia has been associated with liver disease. It is an autosomal recessive deficiency of fumaryl acetoacetase. There is an injurious metabolite, but its exact nature is still unknown. Tyrosinemia presents as either an acute or chronic form.

The acute form of tyrosinemia manifests as rapidly progressive liver failure in infants with vomiting, diarrhea, failure to thrive, abdominal pain, and jaundice. Death is usually within 8 months. Histologically, there is cholestasis with cholestatic rosettes, severe fatty change, occasionally multi-nucleated hepatocytes, and significant fibrosis.

The chronic form of tyrosinemia manifests as renal tubular defects, growth retardation, rickets, and evidence of chronic liver disease. Diagnosis involves identification of succinylacetone in the blood or urine; the enzyme deficiency can also be directly assayed. The histology of chronic tyrosinemia includes a well-established cirrhosis, varying pattern and degree of fatty change, variegated cytoplasm with increased glycogen, cytoplasmic globules, cholestatic rosettes, variably sized nuclei, pericellular fibrosis, bile duct proliferation, scattered mononuclear inflammatory cells, mild siderosis, extramedullary hematopoiesis, and liver cell dysplasia. Children who survive beyond 2 years have a 37% chance of developing hepatocellular carcinoma.

The differential for increased portal eosinophils includes acute rejection and bile duct obstruction. In the case of acute cellular rejection there is the diagnostic triad of portal inflammation, bile duct damage (ductulitis), and venular endotheliitis. It begins as an infiltrate of T-cells (mostly), but large, activated “blast” cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and eosinophils are often present. Severe rejection is indicated by prominent interface hepatitis. The damage to the bile ducts is mediated by the lymphocytes. There is also usually some cholestasis, hepatocyte ballooning, acidophil body formation, and focal necrosis. The most useful feature of this process is the mixed inflammatory response, which was not present in the current case, in which eosinophils by far predominate the histologic picture.

In cases of suspected bile duct obstruction, liver biopsy is rarely performed anymore. Ultrasound and subsequent ERCP are more frequently used to diagnose and treat obstruction. However, with early lesions a liver biopsy may give a clue to the fact that there is obstruction. Histologically in early lesions, early development of portal edema and periductal lamellar collagen fibers is often seen. One also sees inflammatory changes in the portal tracts with a predominance of histiocytes and neutrophils in the portal tracts. However, one can also see eosinophils. Proliferating bile ducts almost always have neutrophils next to, or even within, their basement membranes. Furthermore, an increased alkaline phosphatase in cases of bile duct obstruction is expected.

De novo development of allergies is a known complication of tacrolimus immunosuppression. There is also an association with eosinophilic gastroenteritis. There is a subset of individuals who have peripheral eosinophilia and increased IgE levels, but remain entirely asymptomatic.

Tacrolimus is an 822kDa macrolide derived from a fungus (Streptomyces tsukubaensis). It is structurally different than cyclosporine A, but has similar immunosuppressive properties. It inhibits interleukin-2 induced T-cell activation via binding to immune modulators (“immunophilins”) such as FKBP-FK binding proteins. The complex then binds to calcineurin that, in turn, is inhibited. Calcineurin is important in IL-2 promoter induction, which suppresses T-cells.

The increasing prevalence of transplant patients presenting with new food allergies supports the hypothesis that tacrolimus, and cyclosoprine A to a lesser extent, suppress Th1 lymphocytes by calcineurin inhibitors and promote Th2 lymphocytes and an allergic immune response. Eosinophilia is seen in up to 50% of children receiving tacrolimus immunosuppression but most are asymptomatic.

Treatment includes restriction of items that the person is allergic to, as well as consideration of switching to cyclosporine A, which has a lesser association with development of food allergies.

This patient remains asymptomatic and is a healthy, thriving 14-year-old girl. No specific treatment was deemed necessary for her. Her LFTs were repeated and have since normalized. Her eosinophil count has improved, but remains somewhat elevated. Repeat RAST revealed the aforementioned allergy to cat hair, but with regression of the positive RAST for chocolate. This currently remains a case of tacrolimus-induced eosinophilia without symptoms. She will continue to be monitored by pediatric hepatology and gastroenterology.

Rene Meyers, Pathology Student Fellow, 2006-2007

References

-

Granot E. Yakobovich E. Bardenstein R. Tacrolimus immunosuppression—an association with asymptomatic eosinophilia and elevated total and specific IgE levels. Pediatric Transplantation (2006) 10:690-693.

-

Pathology of the Liver. MacSween RNM. Burt AD, Portmann BC, Ishak KG, Scheuer PJ, and Anothony PP. eds. Elsevier Science Limited, 2002 (Edinburgh).

-

McDiarmid SV. The use of tacrolimus in pediatric liver transplantation. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. (1998) 26:90-102.

-

Saeed SA. Integlia MJ. Pleskow RG. Calenda KA. Rohrer RJ. Dayal Y. and Grand RJ. Tacrolimus-associated eosinophilic gastroenteritis in pediatric liver transplant recipients: role of potential food allergies in pathogenesis. Pediatric Transplantation (2006) 10: 730-735.