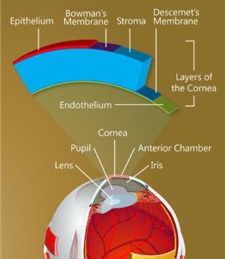

The structure of the cornea.

(Keratomania.com eye diagram by

Chabacano,via Wikimedia Commons.)

On the backside of the cornea is a single layer of cells that plays an all-important role, maintaining just the right fluid balance to keep the cornea transparent so that light can enter the eye. Until recently, it was believed this layer, called the corneal endothelium, is incapable of replacing its damaged cells. As more cells become damaged, the cornea becomes opaque, leading to loss of vision and, ultimately, to as many as 30,000 endothelium transplants a year in the United States alone.

A team of University researchers is exploring the possibility that stem cells on the outer edges of the cornea, given the right stimulation, can migrate into the endothelium to replace damaged cells. (Undifferentiated stem cells develop into specialized cells.) The work raises the possibility of restoring vision without the need for transplants.

The team is led by Amy Kiernan, associate professor of ophthalmology, and includes Jannick Rolland, the Brian J. Thompson Professor of Optical Engineering; Patrice Tankam, a senior scientist in the Center for Visual Science; Changsik Yoon, a graduate student in Rolland's lab; Rebecca Rausch, a graduate student in Kiernan's lab; and Holly Hindman, former associate professor of ophthalmology, now in private practice but still consulting on the project. They are supported with a $75,000 University Research Award. The URA program is designed to help researchers develop preliminary data or proof of concept needed to leverage larger federal or foundation awards to carry a promising project to completion.

There have been tantalizing clinical hints that the corneal endothelium may have regenerative capabilities, Kiernan says. For example, there have been cases in which endothelial transplants failed to engraft, but the cornea cleared up anyway, with regeneration of the endothelium occurring on its own. "So it seems that if something is done that stimulates a progenitor or stem cell population, most likely those in the periphery of the cornea, there is some regenerative capacity in the endothelium -- just based on clinical studies," Kiernan says.

Her team will attempt to identify the potential stem cells that might be stimulated to migrate to the endothelium to repair damage. They will use mouse models from Kiernan's lab in which adult stem cells can be permanently tagged with fluorescent biomarkers and tracked even after they differentiate into other cells. The identification and tracking of those cells will be done by refining a novel imaging approach developed in Rolland's lab. Called Gabor domain optical coherence microscopy, the technology allows rapid, noninvasive imaging of cellular structures beneath the surface of the skin or within the human eye -- in greater detail than traditional imaging with optical coherence tomography.

"Think of it as a high-definition, volumetric imaging," Rolland says. "But we also want to know what kind of cells we are looking at, so we are integrating fluorescence imaging with the high-definition volumetric microscopy so we can do both." The team represents a combination of pertinent expertise: cell development and regeneration (Kiernan and Rausch), imaging (Rolland, Tankam, and Yoon), and the biological basis for corneal and ocular surface diseases in humans (Hindman). The University Research Award funding is helping support graduate students and technicians working on the project, and the cost of mice and supplies. "Pilot funding like this is so important, especially with NIH grants shrinking," Kiernan says.

"It's really helpful to be able to bridge this kind of interdisciplinary effort," says Rolland. "You need to work together a little bit to understand the challenges involved and what you need to do to secure preliminary data, to show we have a pathway. "It takes time to get data, so even a small grant that provides a bridge for a year or two can make a huge difference."