Pediatric Research Newsletter - September 2014

Do Visual Cues Affect Communication and Music Perception in Adolescents with Autism?

Laura B. Silverman, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Pediatrics is conducting research on verbal and nonverbal behaviors to help explain why adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) struggle in social and communicative situations. Everyday social situations can be confusing. The things that people say often have multiple meanings and subtle nuances, making it necessary to use additional sources of information to decode the intended message. Hand gestures, used by people when they talk, provide a robust source of nonverbal information for listeners. The human brain is wired to automatically process a speaker’s gestures and integrate observed gestures with speech to help make sense of what others are trying to communicate. This process of automatic audio-visual integration (integration of what is seen and heard) aids communicative understanding. Since individuals with autism process sensory information differently from typically developing people, they may fail to integrate gesture and speech, possibly contributing to the core social and communicative impairments that are central to the disorder. Dr. Silverman is investigating this question through a series of interdisciplinary research studies funded by the National Institutes of Health and private foundations.

Laura B. Silverman, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Pediatrics is conducting research on verbal and nonverbal behaviors to help explain why adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) struggle in social and communicative situations. Everyday social situations can be confusing. The things that people say often have multiple meanings and subtle nuances, making it necessary to use additional sources of information to decode the intended message. Hand gestures, used by people when they talk, provide a robust source of nonverbal information for listeners. The human brain is wired to automatically process a speaker’s gestures and integrate observed gestures with speech to help make sense of what others are trying to communicate. This process of automatic audio-visual integration (integration of what is seen and heard) aids communicative understanding. Since individuals with autism process sensory information differently from typically developing people, they may fail to integrate gesture and speech, possibly contributing to the core social and communicative impairments that are central to the disorder. Dr. Silverman is investigating this question through a series of interdisciplinary research studies funded by the National Institutes of Health and private foundations.

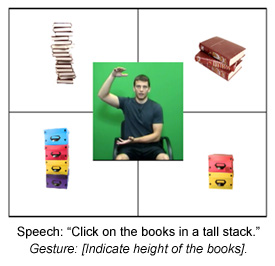

In her Communication and Music Perception study, Dr. Silverman assessed whether adolescents with autism are able to integrate speech with co-expressive hand gestures to construct meaning, and whether seeing a speaker’s gestures helps or hinders their understanding. (Fig. 1) The study used eye-tracking methodologies to record eye movements while adolescents with and without autism played computer games. Study participants watched videos of a person describing a specific picture within a visual array, and were asked to click on the picture that the speaker was describing. Half of the videos that they saw showed a man talking and gesturing, and the other half showed the man just speaking, without accompanying hand movements. This approach allowed researchers to compare participants’ understanding of the speaker’s message in the presence and absence of gesture.

Figure 1. A trial from the computer game that participants

play during the eye-tracking experiment.

Thus far, Dr. Silverman’s research has demonstrated that adolescents with ASD process gesture and speech differently from those who are typically developing. Specifically, participants without autism immediately bound verbal and gestural information and looked at the correct picture more quickly when gesture and speech were both present, compared to when speech occurred alone. The opposite pattern was seen in adolescents with ASD. Viewing hand gestures actually slowed their understanding of the speaker’s message, and it took them longer to select the correct picture when both gesture and speech were present, compared to when speech occurred alone. This finding has important implications for communicating with individuals with ASD, since speakers often demand eye contact or provide additional visual information (such as gestures, signs or pictures) to reinforce their message. It is possible that people with ASD will be more successful listeners if they are permitted to attend to a speaker aurally rather than both visually and aurally.

Dr. Silverman conducted a second set of experiments to see whether audio-visual integration difficulties in autism are specific to language processing or whether they extend to other types of tasks. Just as gesture exerts an influence on speech perception, it can also affect the way that music is experienced. For example, the performance gestures that a musician makes while playing an instrument such as the marimba (an instrument similar to a xylophone), actually alters the listener’s experience of how long a musical note sounds. Notes followed by short hand gestures sound shorter and those followed by long gestures sound longer, even when actual note lengths are the same. Dr. Silverman tested whether adolescents with ASD experience this audio-visual illusion. She found that both adolescents with ASD and those without it perceived notes that were accompanied by longer gestures as sounding longer. This suggests that adolescents with ASD can integrate gestures with musical notes, even though they have trouble integrating gestures with language (as illustrated in the previous study). This differing pattern of audio-visual integration ability in language and musical tasks has implications for underlying neurobiological processes in ASD, since different parts of the brain process language and musical notes.

Research Grants

2010-2014

-

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) 1 R03 (Silverman):

"Sensory Integration and Language Processing in Autism."

Role: Primary Investigator

2010-2013

-

Schmitt Award for Integrative Brain Research (Romanski & Silverman):

"Social and Non-social Sensory Integration: Neuronal Mechanisms and Relevance to Autism."

Role: Co-Primary Investigator

2004-2006

-

Ruth L. Kirschstein Individual Predoctoral National Research Service Award, NIMH 1 F31 (Silverman):

"Gesture Comprehension in High-Functioning Autism."

Role: Primary Investigator

Steiner receives “Basil O’Connor Starter Scholar Award”

Laurie A. Steiner M.D., Assistant Professor of Pediatrics in the Division of Neonatology and a member of the Pediatric Biomedical Research Center has received a Basil O’Connor Starter Scholar Award of the March of Dimes Foundation. This is a highly competitive program and Dr. Steiner’s selection is a testament to the quality and significance of her burgeoning research program. Dr. Steiner is an undergraduate alumnus of the University of Rochester. She received her medical degree from Mount Sinai School of Medicine. She completed her pediatric residency and fellowship in neonatology at Yale, where she was a Pediatric Scientist Development scholar. Her research focuses on genomics and epigenetics of hematopoiesis. Her Basil O’Connor award will support her investigation of the mechanism by which erythropoietin functions in the central nervous system and its potential in the treatment of hypoxic-ischemic-related neurological disease in infants.

Laurie A. Steiner M.D., Assistant Professor of Pediatrics in the Division of Neonatology and a member of the Pediatric Biomedical Research Center has received a Basil O’Connor Starter Scholar Award of the March of Dimes Foundation. This is a highly competitive program and Dr. Steiner’s selection is a testament to the quality and significance of her burgeoning research program. Dr. Steiner is an undergraduate alumnus of the University of Rochester. She received her medical degree from Mount Sinai School of Medicine. She completed her pediatric residency and fellowship in neonatology at Yale, where she was a Pediatric Scientist Development scholar. Her research focuses on genomics and epigenetics of hematopoiesis. Her Basil O’Connor award will support her investigation of the mechanism by which erythropoietin functions in the central nervous system and its potential in the treatment of hypoxic-ischemic-related neurological disease in infants.

Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE) is a common cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality. HIE can be caused by a variety of factors that result in inadequate cerebral oxygenation or blood flow around the time of delivery. Therapeutic options for HIE are limited and surviving infants are at high risk of poor neurodevelopmental outcome. Erythropoietin (EPO) is a glycoprotein hormone that is a key regulator of red blood cell production, and exogenous EPO administration is a well-established therapy for anemia resulting from a variety of etiologies. EPO also has important roles outside of the hematopoietic system. Both EPO and its receptor, EpoR, are highly expressed in the fetal brain and recent studies have demonstrated that EPO is important for normal neural development.

Accumulating evidence suggests that exogenous EPO therapy may improve neurologic outcomes in infants following hypoxic-ischemic injury. Exogenous EPO therapy is neuroprotective in animal models of HIE and clinical trials have suggested that EPO may improve outcomes for infants affected by HIE. Although the molecular mechanisms underlying the action of EPO in the hematopoietic system have been extensively studied, the molecular mechanisms by which EPO acts in the nervous system are not well understood. The goal of Dr. Steiner’s study is to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the neuroprotective effects of EPO in the developing brain.

Department of Pediatrics Highlighted Publications

-

SDF-1 dynamically mediates megakaryocyte niche occupancy and thrombopoiesis at steady-state and following radiation injury.

Niswander LM, Fegan KH, Kingsley PD, McGrath KE, Palis J. Blood 124(2):277-286, 2014. PMID: 24735964

-

School-located influenza vaccination: can collaborative efforts go the distance?

Humiston SG, Poehling KA, Szilagyi PG. Acad Pediatr 14(3):219-20, 2014. PMID: 24767773

-

Cumulative neonatal oxygen exposure predicts response of adult mice infected with influenza A virus.

Maduekwe ET, Buczynski BW, Yee M, Rangasamy T, Stevens TP, Lawrence BP, O'Reilly MA. Pediatr Pulmonol, In Press 2014. PMID: 24850805

-

A community cross-sectional survey of medical problems in 440 children with Down syndrome in New York State.

Roizen NJ, Magyar CI, Kuschner ES, Sulkes SB, Druschel C, van Wijngaarden E, Rodgers L, Diehl A, Lowry R, Hyman SL. J Pediatr, 164(4):871-875, 2014. PMID: 24367984

-

The impact of postnatal antibiotics on the preterm intestinal microbiome.

Dardas M, Gill SR, Grier A, Pryhuber GS, Gill AL, Lee YH, Guillet R. Pediatr Res. 76(2): 150-158, 2014. PMID: 24819377

-

Treatment of Mycoplasma Pneumonia: A Systematic Review.

Biondi E, McCulloh R, Alverson B, Klein A, Dixon A. Pediatrics 133(6):1801-1890, 2014. PMID: 24864174