Safety and Performance Improvement Education

Safety and Performance Improvement Education

As an academic medical center, we are deeply committed to equipping our healthcare workforce with comprehensive education in healthcare safety and performance improvement. To support this mission, the RISE (Rochester Improvement and Safety Education) Assessment—developed here at the University of Rochester—serves as a cornerstone of our educational strategy. This validated, milestone-based tool evaluates four key domains: patient safety, performance improvement, quality assessment, and team effectiveness. By assessing both knowledge and practical experience, the RISE tool enables us to identify specific educational needs across our clinical and non-clinical staff, ensuring that our training programs remain targeted, relevant, and impactful.

In addition to the RISE Assessment, we offer a robust and diverse curriculum designed to meet the evolving needs of our workforce. Educational offerings are available in both online and in-person formats, providing flexibility and accessibility for all learners. Courses range from introductory materials that cover foundational concepts to advanced, skills-based sessions that foster deep expertise and promote continuous improvement in clinical practice and organizational performance.

Healthcare Safety Concepts

Medical Error

A medical error is a failure in the process of care that could lead to harm to a patient.

- It happens when something is done incorrectly (an error of commission) or not done when it should have been (an error of omission).

- Importantly, a medical error may or may not cause harm.

Examples:

- Giving the wrong medication dose.

- Operating on the wrong site.

- Failing to order a needed diagnostic test.

Near Miss (or Close Call)

A near miss is a medical error that was caught or corrected before it reached the patient or caused harm.

- The process failed, but the error did not result in injury because it was intercepted or by luck.

- Near misses are valuable for learning because they reveal system vulnerabilities without patient harm.

Examples:

A nurse almost administers the wrong drug, but notices the error before giving it.

A mislabeled blood sample is identified and corrected before testing.

Adverse Event

An adverse event is an injury or harm to a patient caused by medical management rather than by the underlying disease.

- It represents actual patient harm resulting from care.

- Not all adverse events involve an error — some are unavoidable complications (e.g., an allergic reaction in a patient with no known allergies).

Examples:

- A patient develops an infection after surgery due to poor sterile technique (preventable adverse event).

- A patient has a known side effect from a correctly prescribed medication (non-preventable adverse event).

Just Culture in healthcare is a framework for balancing accountability and learning when errors, near misses, or adverse events occur. It promotes a fair, open, and learning-oriented environment — where staff are encouraged to report mistakes without fear of punishment, while still holding individuals accountable for reckless or intentional behavior. It recognizes that most healthcare errors result from system flaws, not individual negligence.

The main goal is to identify when an error occurs and understand why it occurred and how to fix the system that allowed it. While staff are responsible for their choices and actions, the response to an incident depends on the type of behavior, not the outcome alone. A Just Culture encourages reporting of errors and near misses and builds trust among staff, patients, and leadership.

Three Types of Behaviors in a Just Culture

- Human Error: Unintentional mistake (e.g., slip, lapse, or mistake).

- Response: Console and support the individual; improve systems and training.

- At-Risk Behavior: Choosing to take a shortcut or ignore a rule, believing it’s safe or efficient.

- Response: Coach and educate; modify systems to reduce incentives for risk-taking.

- Reckless Behavior: Choosing to take a shortcut or ignore a rule, believing it’s safe or efficient.

- Response: Disciplinary action or remedial measures.

The Model for Improvement is a simple, yet powerful framework developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) to help healthcare teams make meaningful, measurable improvements in care quality, safety, and efficiency. It’s one of the most widely used models in healthcare quality improvement (QI) projects worldwide.

Three Fundamental Questions

Three fundamental questions guide the thinking and planning part of the improvement work.

1. What are we trying to accomplish?

Defines a clear, specific, time-bound aim.

Example: "Reduce patient falls in the surgical unit by 30% within 6 months."

2. How will we know that a change is an improvement?

Identifies measures (data) to track progress.

Example: Track number of falls per 1,000 patient-days each month.

3. What changes can we make that will result in improvement?

Generates ideas for change to test.

Example: Implement hourly rounding, use non-slip socks, improve lighting

PDSA Cycle

The PDSA cycle helps teams test changes on a small scale, learn from them, and adjust as needed.

Plan

Plan the test or observation, including who, what, when, and where. Predict what will happen.

Example: Plan to test hourly rounding on one unit for 1 week.

Do

Carry out the plan; document what happened.

Example: Staff perform hourly rounding as planned.

Study

Analyze data, compare results to predictions, summarize learning.

Example: Falls decreased slightly; staff reported better communication.

Act

Decide whether to adopt, adapt, or abandon the change

Example: Adapt the rounding process and test again on another shift.

These cycles are repeated to refine and spread improvements until desired outcomes are achieved.

Root Cause Analysis (RCA) in healthcare is a retrospective investigation of adverse events, errors, or near misses that seeks to understand what happened, why it happened, and what can be done to prevent recurrence. It’s a core patient safety tool that shifts the focus from individual blame to understanding system and process failures that allowed an event to occur. RCA is typically performed after serious adverse or sentinel events, significant near misses that could have caused serious harm, or patterns of recurring issues that signal system problems.

The purpose of RCA is to identify the "root causes" (not just the symptoms) of an incident or event, understand system weaknesses that contributed to the event, develop targeted, sustainable corrective actions to improve safety and quality, and promote a culture of learning, not punishment.

Steps

- Identify and report the event: The event is detected and reported through the hospital’s event reporting system.

- Assemble the RCA team: A multidisciplinary team is formed (nurses, physicians, pharmacists, risk managers, etc.). The team should be objective and not punitive.

- Collect data: Gather facts through interviews, medical record review, and analysis of policies, equipment, and the environment.

- Create a timeline (event flow diagram): Map out what happened, step by step, to identify where failures occurred

- Identify contributing factors: Look at human, technical, organizational, and environmental factors that played a role.

- Determine root causes: Ask “Why?” repeatedly (often using the Five Whys or Fishbone Diagram) to get to the true underlying issues.

- Develop action plan: Create specific, measurable corrective actions that address the root causes (e.g., policy changes, training, equipment redesign).

- Implement and monitor: Put the plan into practice and track results to ensure the issue is resolved and improvements are sustained.

Run charts and control charts are both visual tools used in healthcare quality improvement (QI) to track data over time and determine whether changes lead to real improvement or just random variation. They help teams see trends, patterns, and stability in healthcare processes — such as infection rates, medication errors, wait times, or patient satisfaction scores.

Run Charts

Run Charts

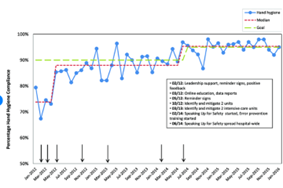

A run chart is a line graph that displays data in time order (e.g., months or quarters) to show how a process performs over time. It’s often the first tool used in improvement work because it’s simple, quick, and doesn’t require complex statistics. The purpose of a run chart is to detect trends, shifts, or cycles in performance. They also help determine whether observed changes are due to real improvement or just random fluctuation. Finally, they are used to assess the impact of interventions over time.

Control Charts

Control Charts

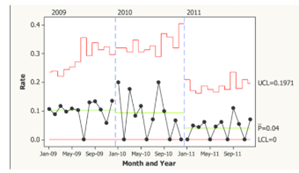

A control chart is an advanced form of a run chart that adds statistical control limits to distinguish common cause variation (natural, random variation) from special cause variation (signals of real change). It’s used when you need more precise, statistical monitoring of process performance. The purpose of using a control chart is to determine whether a process is in control (stable) or out of control (unstable). It is also used to identify when special cause variation exists and requires investigation. Finally, control charts help to verify whether changes lead to sustained improvement.

Summary

A run chart plots data over time with a median line. It helps detect early trends and assess the impact of change. A control chart adds control limits to identify statistical variation. It is used long term to monitor if compliance stays within acceptable limits.

Situation monitoring is a key concept in TeamSTEPPS®, which is a teamwork and communication system developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to improve safety and performance in healthcare teams.

Situation Monitoring is the process of actively scanning and assessing elements of the environment to gain information, understand what is going on, and maintain awareness to support team functioning. In other words, it means constantly paying attention to what’s happening around you — with the patient, the team, the environment, and tasks — so you can anticipate problems, recognize changes, and respond appropriately. The goal is to detect early signs of risk or error.

There are 4 components of situation monitoring:

- S – Status of the patient: Vital signs, history, medications, physical condition, plan of care, psychosocial status

- T – Team members: Fatigue, workload, stress level, performance, skill, communication

- E – Environment: Facility information, equipment status, administrative info, human resources, triage acuity, safety

- P – Progress toward goal: Status of the team’s tasks and goals, timeline, need for plan adjustments

Example in Practice

A nurse in an operating room notices that the patient’s blood pressure is dropping, the surgeon is busy, and anesthesia is adjusting medications. The nurse calls attention to the change ("BP dropping to 80/40") — this act of observing, recognizing, and communicating is situation monitoring, which helps the team maintain situational awareness and respond effectively.

Also see: https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps-program/index.html

Closed-loop communication is a key concept in TeamSTEPPS®, which is a teamwork and communication system developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to improve safety and performance in healthcare teams.

Closed-loop communication is a communication technique in which the sender sends a message, the receiver acknowledges and confirms it, and the sender verifies that the message was received correctly. It ensures that information is accurately transmitted, received, and understood.

The Three Key Steps of Closed-Loop Communication

- Sender: Clearly states a message or request. Example: "Give 1 mg of epinephrine IV push now."

- Receiver: Receives the message and verbalizes back what they heard. Example: "Giving 1 mg of epinephrine IV push now."

- Sender: Confirms that the receiver’s response is correct. Example: "Correct, thank you."

Closed-loop communication in healthcare is important because it ensures clarity during critical tasks, reduces errors caused by miscommunication, and reinforces team accountability and situational awareness.

Also see: https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps-program/index.html

In healthcare, disclosure refers to the process of openly communicating with a patient (and/or their family) when an adverse event, error, or unexpected outcome occurs during medical care.

It’s a key element of ethical, patient-centered, and transparent healthcare practice.

Types of Disclosures

- Full Disclosure (Open Disclosure)

- Communication after an adverse event or medical error that caused or could cause harm.

- Required Disclosure

- Some situations must be disclosed by law or hospital policy

- Voluntary Disclosure

- When providers disclose minor or near-miss incidents that may not be legally required but

are ethically important to share.

Key Components of Disclosure

- Prompt communication – As soon as the event is recognized.

- Explanation of facts – What is known about what happened.

- Acknowledgment of harm or error – Clear and honest description.

- Expression of empathy and apology – Sincere regret for the outcome.

- Outline of next steps – Medical management, investigation, and prevention efforts.

- Follow-up – Ongoing updates as more information becomes available.

Why Disclosure Matters

- Ethical obligation: Honesty and respect for patient autonomy.

- Legal protection: Open communication can reduce malpractice claims and foster trust.

- Trust and transparency: Maintains the integrity of the patient–provider relationship.

- Learning opportunity: Helps healthcare teams identify and address system weaknesses.

Event reporting is the process by which healthcare workers document incidents that could—or did—result in harm to a patient, staff member, or visitor. It’s a key part of patient safety and quality improvement programs.

Main Goals

- Identify risks and unsafe trends before serious harm occurs.

- Understand root causes through analysis of reported incidents.

- Implement system-wide improvements (e.g., protocol updates, staff training).

- Promote a culture of safety, where staff feel safe to report errors without fear of punishment.

What to Report

- Adverse Events

- Medical Errors

- Near Misses (Close Calls)

- Unsafe Conditions or Hazards

- Sentinel Events – Serious, unexpected events causing death or major injury.

How It Works (Typical Process)

- Event Occurs: A staff member observes or is involved in an incident.

- Report Submission: The staff member submits a confidential report (usually electronically).

- Review and Triage: The patient safety or risk management team reviews the report.

- Investigation: A root cause analysis (RCA) or similar review may be conducted for serious events.

- Action and Feedback: Findings are shared, and preventive actions are implemented.

Hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) are medical problems or complications that develop during a patient’s stay in the hospital and were not present at the time of admission. They indicate lapses in patient safety and/or quality of care. Some examples of HAC include pressure injuries, falls and trauma, veinous thromboembolism (VTE), and sepsis after surgery.

Hospital Acquired infections (HAI) are a specific type of HAC. Hospital-acquired infections (also called nosocomial infections) are infections that patients get while receiving treatment for other conditions in a healthcare facility. The most common types of HAI are catheter associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI), central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI), Clostridioides difficile infection (CDIFF) and surgical site infection (SSI).

HAI can be caused by contaminated hands of healthcare workers, improper sterilization of instruments, prolonged use of catheters or central lines, and resistant organisms. Preventive measures include strict hand hygiene, adherence to catheter and line insertion and maintenance bundles, sterile surgical techniques, and antibiotic stewardship programs.