Cancer Biology, thanks to Green Lizards

What can green lizards and “dark matter” teach us about cancer?

Gene Study Points Researchers to New Pathway for Leukemia

Leukemia is one of the hardest cancers to treat, but scientists have discovered a new, targetable pathway in one of the worst subtypes of the disease.

Chang Receives Patent for Prostate Cancer Treatment Method

This month, Chawnshang Chang, Ph.D. received a U.S. patent for a new way to treat prostate cancer.

His methods aim to both treat prostate cancer patients and keep it from coming back.

In his description Chang notes that patients who are treated with the commonly used method of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) often experience a return, even after remission.

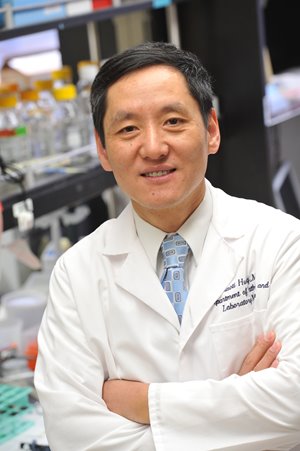

Alumni Spotlight: Dr. Jiaoti Huang, Pathology Chair at Duke University

Some pathologists find themselves torn between research and clinical practice, but Dr. Jiaoti Huang, MD, PhD isn't one of them.

“If things work well, you don’t have to spend a lot of effort balancing the work,” he said. “For me, the more clinical work I do the more problems and issues that I discover for my research.”

Labs Play Critical Role in Lymphoma Immunotherapy Trial

UR Medicine Central Labs and UR Medicine Labs have been providing essential, behind-the-scenes services for a cancer immunotherapy trial that recently received a lot of local publicity.