Notes from the Director - Archive

A Note From The Director October 2023

(Photo by parent of the children, with permission.)

A Positive Sign

While walking my dog every day, I see a positive sign. It’s in the photo above. There’s a traffic sign for a school crossing. Along with that is a crossing guard helping kids to walk or bike safely to RCSD School #23. These are new developments, made necessary by the increasing number of families in the middle-class Park Ave. neighborhood sending their children to the local public school. Why does this matter?

Walkability and active transportation to school are nice things to see for increasing physical fitness. And there are bigger implications. Two new books—Poverty, by America and Excluded—highlight how socioeconomic integration is a way to help level the playing field and decrease poverty in the US. Decades of research on education show that socioeconomic integration of schools yields huge benefits for poor children without resulting in lower performance for middle-class kids. Similarly, overcoming exclusionary zoning by creating mixed-income communities can lift poor families out of poverty. These are Win/Win solutions.

Many people have opposed such changes for many years. But it turns out that the numerous feared downsides (increased crime, decreased property values, etc.) can be avoided. These concerns do not materialize in the well-documented examples like the affordable housing development in Mt. Laurel, NJ or the economically integrated schools in Raleigh, NC. As Heather McGhee noted in the book The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together, segregation costs everyone regardless of color. That is a Lose/Lose scenario.

On my daily perambulation, I see important elements of what these anti-poverty books are advocating. Within a fifteen-minute walk of School 23 or Genesee Community Charter School are single-family homes, apartment buildings, mansions, public housing, duplexes, etc. I feel like we should celebrate positive signs and build on them.

This does not mean ignoring obstacles. As James Baldwin said, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” Over the last few years, we have all heard a lot about the mid-20th-century problem of redlining. So, we are getting better at facing the past. As we do so, the question becomes how well we can face the present and build a better future. The decades since redlining have not made segregation disappear. Voluntary socioeconomic integration can start the process of flipping the vicious cycle of concentrated intergenerational poverty into a virtuous spiral of shared prosperity.

A few children crossing the road will not by itself transform the system overnight. But launching a big change has to start somewhere, and sometimes it’s with very small steps.

A Note From The Director September 2022

Detecting Nothingburgers

I recently read a new book called The Voltage Effect: How to Make Good Ideas Great and Great Ideas Scale. As regular readers of our newsletter know, how to scale up good projects is of great interest to us here at the Hoekelman Center. We even have a little acronym. SCALE: Situate, Collaborate, Advocate, Launch, Evaluate. In the last edition, I wrote about Situate. This time, I’ll take on Evaluate. In general, nobody wants to talk about this, but it’s essential and it can be easy. The key concepts don’t involve any math or statistics.

One of the main examples of scaling discussed in The Voltage Effect is the DARE program. DARE (Drug Abuse Resistance Education) was remarkable for its enormous reach and longevity. Millions of children across the US participated in this for decades. It’s well established now that the original DARE had pretty much zero impact on drug use. Hence the question for people who want to help kids is how to keep things like that from scaling up. To answer this, The Voltage Effect author describes DARE as a "false positive."

He tells the story of how in the 80s someone did an evaluation of the DARE program in Honolulu. The results were so good that DARE wound up getting copied all over the country. It was a “false positive” because even though it worked in Hawaii, that success could not be replicated on a larger scale. “False positives” for scaling are possible. You can have a program that’s super successful because of a charismatic leader, and that’s great but you can’t put that secret sauce of charisma in a bottle, and so you can’t replicate the program in other places. The moral of the story is to watch out for these one-hit-wonder “false positives.”

The problem is that this story is wrong. For the Hawaii 5-0 version of DARE to count as a false positive, it would have to have been super successful. But was it? Let’s evaluate that claim.

The first question to ask is “What’s the outcome?” Well, that’s not very hard to figure out. DARE materials tell us the objective was “to keep kids off drugs,” and “drug abuse resistance” is right there in the name. Therefore, the relevant outcome is drug use. If DARE works, a smaller percentage of kids who go through DARE will use drugs than the percent using drugs in a control group. So how did the Honolulu study determine drug use? They didn’t. They didn’t even try. Not even by self-report.

You can stop there.

Whatever else is in the Honolulu report doesn’t really matter. It’s not strong evidence that DARE works. It’s not a “false positive” because it’s not even measuring the relevant outcome. It can’t be positive or negative. It’s not a basis for deciding one way or another about launching a nationwide program. See, that was easy. No math.

Well, you say, there must have been something to the Honolulu report. Okay, let’s look it up online and read it. Oops! You can’t. It was never published. That’s another big red flag. I’m not saying that appearing in an academic journal is a guarantee of truth. But I can tell you from personal experience that peer-review can be grueling. And the point of it is to improve the quality of what gets published. So, looking at reports that just skip that whole process is asking to make your decision-making iffier than necessary.

If you look for the Honolulu report, what you can find on Google Scholar is the one-paragraph abstract. I quote its conclusions here:

“While results were not definitive, there was support favoring the program's preventive potential. The program was educational, providing students with skills and information they could and did use in various situations. Participants found the program enjoyable and actively engaged with police officers in a positive, constructive learning environment. Overall, results suggest that DARE provides children with information and skills that maximize their potential for adopting healthful, drug-free habits.”

You might have noticed right away that the authors are not saying that they did prevent drug use. They claim the program provided knowledge and skills. That may be true. But without some prior strong evidence that knowledge about drugs leads to keeping kids off drugs, that’s not a valid intermediate outcome. Kids “found the program enjoyable.” That’s nice, but so what? Kids find many activities enjoyable. If this report was the basis for expanding DARE all over the country, it’s not because the evaluation was a strong positive, false or otherwise.

The review paper referenced below from the American Journal of Public Health lists more ways that the Honolulu report is relatively weak evidence, but we don’t even need to get into those. Just based on the very simple analysis we conducted above, we can tell that Honolulu’s DARE experience should never have been the basis for a gigantic national scale-up.

As a result, the lesson is not about avoiding “false positives.” It’s about avoiding nothing-burgers. Oftentimes, all you need to do for that is to ask “What’s the outcome?” The outcome is the stuff in the middle of the burger. Could be anything you want. Maybe it’s beef, maybe it’s a mushroom. Whatever it is, it shouldn’t be nothing. You’re not buying the burger for the bun.

References

- S T Ennett, N S Tobler, C L Ringwalt, and R L FlewellingCenter for Social Research and Policy Analysis, Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-2194. “How effective is drug abuse resistance education? A meta-analysis of Project DARE outcome evaluations.”, American Journal of Public Health 84, no. 9 (September 1, 1994): pp. 1394-1401. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.84.9.1394

- Nordrum, A. (2014). The new DARE program—This one works. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-new-d-a-r-e-program-this-one-works/

A Note From the Director February 2022 Doing Pre-K The Wrong Way Doesn't Work

This past week, a CARE Track graduate texted me about a disturbing news item on NPR. A rigorous study of thousands of Tennessee children followed to 6th grade found that attending free pre-K was harmful. It led to worse test results, more behavior problems, and more placements in special ed. There is a ton to unpack in this story.

When asked to explain why free government pre-K was worse than nothing, the lead researcher conjectured that the preschoolers were spending too much time being lectured to, getting disciplined, and standing in line for the bathroom. "Whoever thought that you could provide a 4-year-old from an impoverished family with 5 1/2 hours a day, nine months a year of preschool, and close the achievement gap…?" Her conclusion was that “We might actually get better results from simply letting little children play.”

The underlying issue is a problem of scaling. The effectiveness of what the article called “showcase pilot programs” like Perry High/Scope and Abecederian is not being disputed. The argument here is that it’s possible to get good long-term academic and social outcomes, but only in small-scale experiments, not in population-level services. This implies that there was something so special in those showcase programs that it can’t be replicated.

Let’s consider that. Why did the showcase programs work? The people who evaluated Perry High/Scope answered this in their causal model: "high-quality preschool programs do lead to an improvement in children's motivation, but because of, not instead of, improvement in children's intellectual performance.” [1]

The italics are in the original report. They’re there because the fear that preschool education could be bad for kids is not new. “At the time the Perry Project began, there was considerable concern on the part of nursery educators about the "pressures" a program as structured as the Cognitively Oriented Curriculum would inflict upon the children. There were dire predictions of permanent emotional damage to the experimental children.”

At this point, it helps to keep two things in mind. Firstly, the whole context of this is the “achievement gap.” Children born into poverty in the U.S. are, on average, way behind the starting line at the beginning of kindergarten vis-à-vis their more affluent peers. The middle-class and rich kids have a head start, and that generally works out for them very nicely, presumably without permanent emotional damage. Secondly, we know that Perry improved social-emotional long-term outcomes AND improved early cognitive development. So there does not appear to be an either/or here. We can teach the ABCs to little children from impoverished families without scarring them psychologically for life.

Not only that, but the point of the italicized lesson from Perry High/Scope is that the social-emotional gains are because of the intellectual gains. How does that work? By mastering basic tasks like knowing their letters and writing their names, the children became comfortable starting kindergarten and were therefore less likely to act out at school. This is “the foundation of school success, reducing placements [in special ed] and leading [to] a higher level of schooling.” And what is the High/Scope curriculum that achieves this? The core concept is Active Learning. It is not “simply letting little children play.” But neither is it an adult lecturing to a group of children. Pre-K teachers in the Active Learning model are doing a lot of work so that what looks like play from the child’s perspective is a series of learning moments. As the National Association for the Education of Young Children recognizes “It’s not play versus learning, but play and learning.” Fortunately, there are masterful preschool teachers in Rochester replicating the High/Scope methods.

In contrast, the pre-K programs described by the researcher in the NPR story seem to be doing the opposite of the Active Learning approach. They are apparently drilling the children with information instead of scaffolding play with learning; they are plugging the kids into the special ed system instead of instilling them with the confidence that comes from competence; they are spending a lot of time disciplining them to stand still instead of allowing them to explore activity stations. If all that is true, it is not a mystery why the “showcase programs” worked but Tennessee’s pre-K didn’t. “Teaching for the test” can produce some good short-term results but make long-term outcomes worse.

This story about expansion of pre-K is a cautionary tale, but I don’t think that we should throw the baby out with the bathwater and give up on trying to close the equity gap in early learning. The challenge is to scale up effective, feasible and acceptable practices. This is not easy to do. For thinking about how to scale up projects, I use the SCALE framework: Situate, Collaborate, Advocate, Launch, and Evaluate. In this note, I only touched on the first letter in the acronym: Situating, getting the lay of the land by looking at what is already out there. The Hoekelman Center is currently working with multiple community-based partners to apply the SCALE framework in small ways for various projects, including some related to early education. I expect our results will be encouraging.

[1] Schweinhart, Lawrence J. Significant Benefits: The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study through Age 27. Monographs of the High/Scope Educational Research Foundation, No. Ten. High/Scope Educational Research Foundation, 600 North River Street, Ypsilanti, MI 48198-2898, 1993.

[1] Epstein, Ann S. The Intentional Teacher. NAEYC, 2019

A Note From The Director October 2021, Revising the Future

There’s a podcast called Revisionist History and it got me thinking that revising history is interesting but revising the future would be much better. The podcast’s host is best-selling non-fiction writer Malcolm Gladwell. In one of the episodes, he interviews a brilliant boy named Carlos who lives in an impoverished Southern California city with a low-performing school district. Carlos’s predictably dismal educational destiny is turned around by a wealthy and well-connected Hollywood lawyer who gets personally involved in his case and, among other things, sends Carlos to private school.

It’s a touching rescue narrative, and it does a good job of highlighting the problem of how every year in this country we waste the “human capital” of many thousands of children. Kids like Carlos are bright enough to benefit from going to college and would like to, but often they don’t get the chance because of all the obstacles that go along with growing up in poverty. Unfortunately, assigning generous bigshot lawyers to individual children is not a scalable solution.

One promising approach to moving the needle a little bit on this problem is the concept of “college matching.” This comes from research that investigated why high-performing high school students from low-performing districts tended to drop out of college even after they applied and got in. One finding was that they often attended colleges that were not good matches for them academically, either because the students aimed too high or too low. Based on high school scores, potential colleges can be divided into the three categories of reach, par, and safety for each applicant. Going to a “par” college increases the chances of staying until graduation. These findings have given rise to multiple interventions designed to help kids find a good match.

This school year, we are beginning a project to pilot the college matching concept locally at Wilson Magnet High School in Rochester. In addition to the counselors and others at Wilson, we will be partnering with multiple programs, like Rochester College Access Network and Upward Bound, that already provide help with financial aid applications and academic mentoring.

In our model, volunteers from local colleges—many first-generation university students—will offer “coaching” to high school seniors on the college application process. For example, one resource already available in the RCSD is the computer program Naviance, that contains all kinds of data on colleges and can help with the matching process. Research indicates, however, that it works better if students receive guidance on how to use it. Our college-student volunteers are experts on various aspects of getting into college nowadays, including how to use the latest tech. VISTA Americorps volunteer Minhtam Tran is working with us in the Hoekelman Center this year, and has been busy recruiting the “coaches” who are excited to start.

College education is a major predictor of wealth and health. Ultimately, the long-term solution to improving equity in college access is to decrease child poverty and ensure a democracy of opportunity with upward mobility. In the meantime, it is worthwhile to look for points of leverage where we can work together to mobilize existing resources in a way that produces significant benefits now and here.

A Note From The Director March 2021

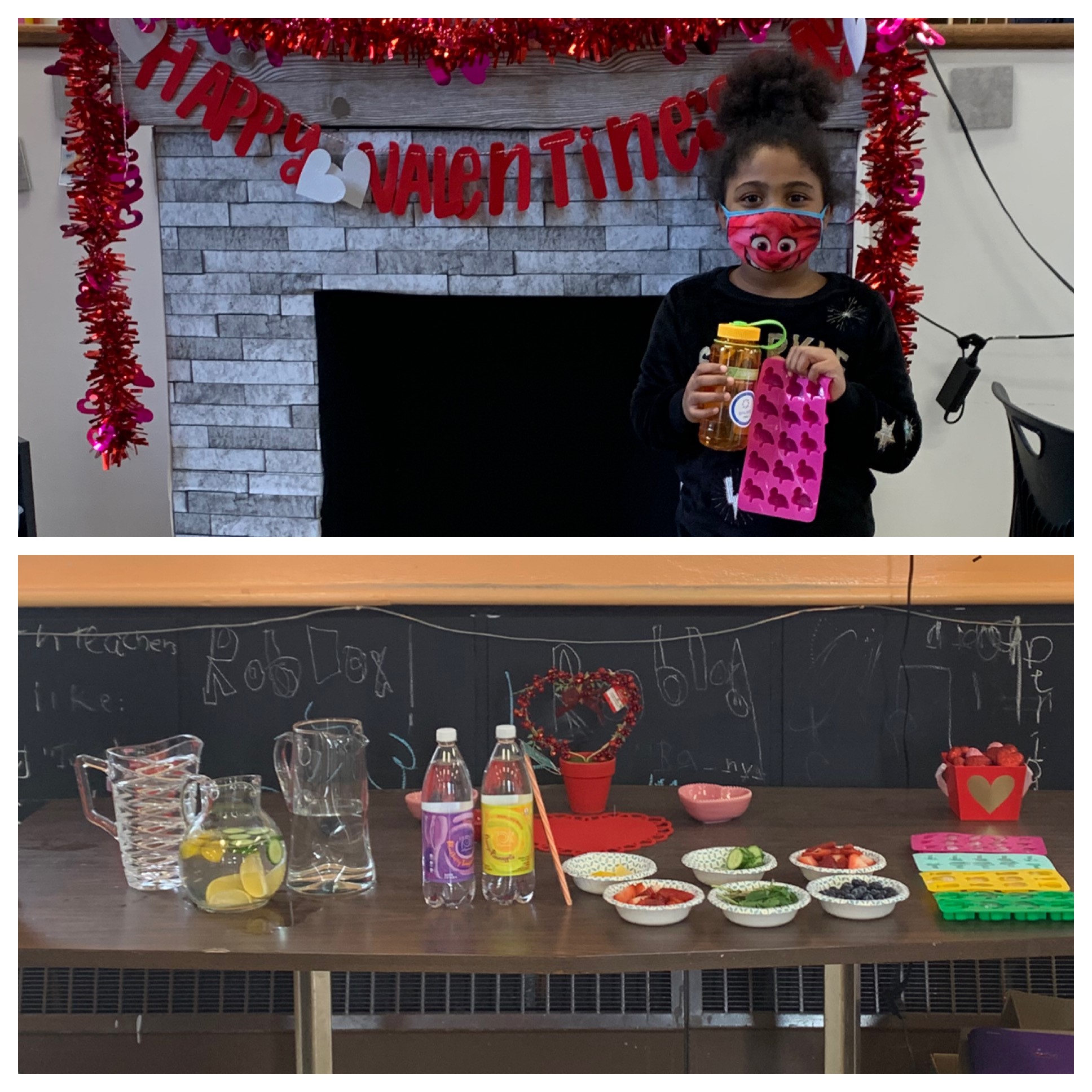

Pictured above: Water taste test with Cameron Community Ministries

Clear As Ice

I saw a documentary recently about political propaganda, and one of the characters explained that it didn’t matter if he was spreading lies across America because all the philosophers will tell you that objective reality doesn’t exist. I beg to differ. There’s a type of philosophy—natural philosophy, usually called “science”—that specializes in studying objective reality. And it helps for figuring out what’s true.

A medical student asked me recently whether she should trust a book she was reading about the causes of obesity (The Case Against Sugar). The book seemed to be contradicting many things she had heard her whole life. I knew the book and said “Yes, it can be trusted,” but then I explained how I had looked up some of the key scientific studies cited in the book and verified that they said what they were supposed to say. Science is the habit of skepticism. Trust is based on evidence. Human nutrition research seems notoriously self-contradictory, but that doesn’t mean one should give up and say “eat and drink whatever you want because no one knows anything.” We do know stuff. We can look at the overall weight of the best available evidence. If we do, we find there are some things where there’s a ton of knowledge from different types of research pointing in the same direction—sugary beverages, for example.

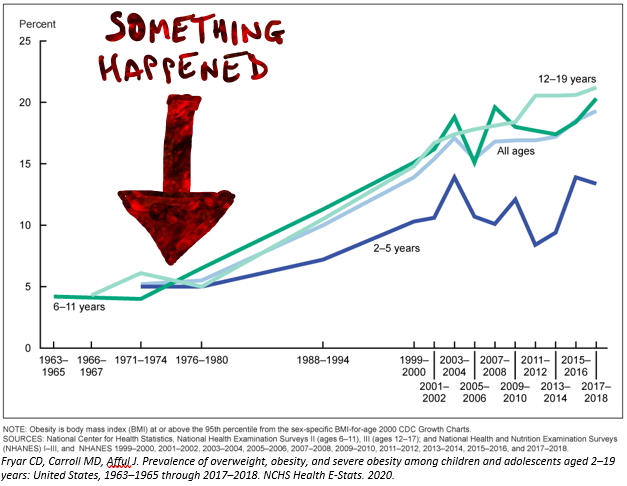

Sugary beverages are a problem. The graph shows one of the clues supporting that.

Around 1980 some big change affected the U.S. population (on average). One suspected cause of the obesity epidemic is a huge rise in sugar consumption, particularly via beverages. So, what do we do about it?

From a public health perspective, we think about lowering barriers to healthy behaviors and raising barriers to unhealthy ones. Therefore, we should be trying to figure out how to keep sweet drinks away from kids. This is hard. A recent article in the Democrat & Chronicle included a photo of what some local school kids are getting for lunch during the current COVID crisis, and the meal included two beverages: one was sugar-sweetened chocolate milk, and the other was some kind of juice drink. Even if we could reduce exposure to sugary drinks, we would need to provide a healthy substitute, like water. How do we help make water a more typical choice for what children drink?

This is the question animating one of the current CARE projects. Recently, Dr. Sophie O’Rourke went to Cameron Community Ministries and did a sort of taste test of different types of water with the kids there. Here’s what she found:

- Fruit-flavored fizzy water: Hated it

- Fruit-infused water: No, thank you

- Regular tap water: Okay

- Ice-water: Can I have more water please?

- Ice-water with novelty ice “cubes” drunk out of your own colorful bottle: Yay!

People sometimes don’t even want to try projects like this because they believe the kids will refuse anything that isn’t sweet. However, existing research shows that having more and better drinking fountains in schools does help to get kids drinking water and might even help decrease obesity. In any case, it’s clear that water is healthier than sugary drinks. But right now, lots of kids are not at school, and even then, they have access to many beverages. We can just give up against the obesity epidemic and all the diabetes and heart attacks to follow, or we can look to the public health science. This CARE project is not scientific research, but it is guided by the available knowledge. Moreover, it is a great first step in local community action for finding a feasible and acceptable step forward in fighting an enormous public health problem. And it was fun! (Thanks to our friends at Cameron for making this non-remote event possible. Thanks to Rochester-based Nalgene for donating bottles.)

As astronomer Neil DeGrasse Tyson says, “The good thing about science is that it’s true whether or not you believe in it.” The truths in science are not absolute and unchanging. Science is a living process of moving from less truth to more truth. It involves human beings so it can suffer from errors and corruption. But overall, it works pretty well for helping us understand the Universe and can help for making things better here and now.

Take care,

Andy Aligne

A Note From The Director October 2020

Director of the Hoekelman Center, Andy Aligne, M.D., M.P.H., was invited to speak on WXXI's program Connections with Evan Dawson regarding the pandemic. You can take a listen here "Coronavirus and Population Density"

What Is Epidemiology?

One of the silver linings that I hoped would come out of this disastrous epidemic was a better public understanding of epidemiology, but that doesn’t seem to be panning out, as this recent quote from The New York Times illustrates,

“But observational studies can show only correlations, not cause and effect.” (NYT 9/1/2020)

A variation on the above sentence appears pretty much every week in the science section. I understand why they say this: because there are all these studies where one thing is associated with another, but it doesn’t mean that the first caused the second. A basic lesson in science is that simple correlation by itself is not sufficient proof of causation. True enough. If several people play their birthdays and win the Lotto, that doesn’t prove that playing your birthday is a sure-fire way to win the Lotto. But that truism doesn't justify the logic leap to implying that observational epidemiologic studies can't provide actionable evidence of causality, or that only randomized trials can do that.

Epidemiology, generally speaking, is about looking at the big picture of entire communities. It tries to answer questions like How do we prevent epidemics? Going back to the work of pioneers like Florence Nightingale, epidemiologic studies led to public health and hygiene interventions that enormously increased life expectancy by decreasing deaths from infectious diseases.

Since then, epidemiology has saved more millions of lives by uncovering the preventable causes of non-infectious diseases. For example, it was epidemiologic studies that established that cigarette smoking was the main underlying cause of the global lung cancer pandemic. It was epidemiologic studies that determined that belly-sleeping was the cause of the SIDS epidemic and then established that Back to Sleep was an effective solution. I could go on.

In terms of the current COVID catastrophe, there are lessons from the epidemiology of previous pandemics that could be helpful. For example, I had the opportunity to be on the radio recently because WXXI’s Connections did a show on the impact of population density on COVID, and I talked about how the real issue is overcrowding, not population density. I wrote a research article about this in the American Journal of Public Health regarding the 1918 flu. The distinction matters for health policy because it’s not cities or tall buildings that are the problem so much as homes, workplaces or any locations where too many people are packed in together. As a recent article in The Atlantic pointed out, the common theme around the world in outbreaks that have been driving the pandemic is “the three Cs”: crowds in closed spaces in close contact. Nations that have been using this understanding to fight the pandemic have been more successful in controlling the contagion than those that haven’t.

If we ever figure out what made the COVID-19 pandemic as severe as it is and how to keep similar future pandemics from occurring in the first place, observational epidemiology will probably play a role in that. Epidemiology is an amazing science that saves lives. Respect.

P.S. For more info on epidemiology, the Hoekelman Center has a number of books on the topic and the CDC has great online resources.

A Note From The Director January 2020

Pictured above: Children from the Cyclopedia Program created from a CARE Project by Cappy Collins, MD, in the Rochester Review Magazine January/February 2013

The Social Determinants of Health (SDoH)

What Should We Do About Them, and How Does One Teach That?

As I write this, a Viewpoint in JAMA points out that there’s some confusion about SDoH (Silverstein, NAS). A huge focus lately has been on “screening for SDoH” in the medical setting, but there’s not a ton of evidence for this approach and even some concern that it could do more harm than good (Davidson). So what’s the problem with SDoH “screening”?...

First of all, it doesn’t always work very well for accurately identifying social risks. Why not? There are multiple potential reasons:

- People might be afraid to reveal that they don’t have enough to eat, for example, because they worry that they could wind up getting their children taken away.

- People are used to the conditions they’re used to and might have a different definition of “normal.”

- A few years ago, CARE residents Francis Coyne and Andy Peckham along with some medical students, and in consultation with Dr. Arvin Garg the leading expert on the WECARE survey tool-did a project on SDoH screening. They found that even when people did reveal social risks, they often didn’t want any assistance because they expected their problems to be temporary.

- The questions can be stigmatizing, especially if only administered in high risk populations.

- Even when people answer accurately and ask for help, it’s not obvious how to connect them to resources or that these resources will be effective for resolving their problems and improving health outcomes.

- The doctor’s time could already be stretched pretty thin. Adding one more list of tasks to the clinical encounter would just make it more rushed.

- Investing in SDoH screening could divert attention and resources from preventive community-level action.

So what’s the solution? I would propose that if health professionals are to become effective partners in addressing SDoH then they first need a basic understanding of evidence-based community-health. And that’s what we’ve been teaching in CARE track for all these years!

To deliver that education, we go beyond the walls of the hospital or doctor’s office and partner with community-based organizations and individuals. This was the insight of Anne E. Dyson, a pediatrician and philanthropist who founded the Dyson Initiative to promote this type of training. At this 20th Annual Dyson Day we salute her vision and celebrate it by looking at the success we’ve had with almost 200 participants in the CARE track.

Our special guest speakers for Dyson Day this year are Dr. Sara Horstmann and Dr. Cappy Collins who will be talking about their wonderful CARE projects and how they have continued to use what they learned in CARE to keep doing and teaching community health and advocacy.

References:

- Addressing Social Determinants to Improve Population Health, The Balance Between Clinical Care and Public Health. Michael Silverstein, MD, MPH, Heather E. Hsu, MD, MPH. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2757035

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2019. Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25467.

- Screening for Social Determinants of Health, The Known and Unknown. Katrina W. Davidson, PhD, MASc, Thomas McGinn, MD, MPH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31465095

A Note From The Director October 2019

Pictured above: Dr. Aligne pointing at a plaque which commemorates the site in the University of Rochester where the HIB vaccine was invented "leading to the eradication of the Haemophilus Influenza Type b disease in children."

Opioids and "Antivaxxers"

There is a strong case for childhood vaccines like the Hib shot, which was invented here in Rochester, and prevents deadly epiglottitis and meningitis. Nevertheless, according to the medical literature, when pediatricians take the time to give information to vaccine-hesitant parents, it doesn’t seem to accomplish much in terms of changing minds but it does tend to increase burnout among the doctors. So what to do?

In my course on project planning, I often say, “Don’t reinvent the wheel or the Hindenburg!” What I mean by that is to resist the urge to rush into action. Instead, I want folks to start by looking stuff up so they can do what works best, or at least avoid repeating proven mistakes. When the literature does not provide specific solutions, we need to fall back on general principles.

Going back to Aristotle, the three key components of persuasive argument are Ethos (credibility with the audience), Pathos (emotional connection) and Logos (facts and such)—in that order. Using this framework, if we want to understand a breakdown in communication between pediatricians and parents, we shouldn’t start by looking at vaccine handouts, or even with sad stories about sick children. We should start by looking for any reasons the public might distrust the medical establishment.

Unfortunately, a casual glance at the daily news yields plenty of reasons. As I write this today, the headlines are about new research showing how red meat is not actually bad for you. Apparently, the nutrition experts telling us that red meat causes deadly heart attacks have been basing their recommendations on very weak evidence. The news article didn’t go over the actual evidence; it just quoted doctors going back and forth over how misguided their opponents are. All the average reader could conclude is that many of the experts are wrong—one way or the other.

Even more disturbing is the ongoing saga of the opioid crisis that has been dominating the news for weeks. This manufactured epidemic caused hundreds of thousands of deaths and millions of severely disrupted lives. I recently read the book American Overdose, and what that makes clear is that the responsibility for this disaster goes way beyond the Sackler family and Big Pharma. The list includes many doctors, including medical school professors and leaders of organized medicine, the FDA, hospitals, pharmacies, drug distributors, etc.

Given current realities like the opioid crisis, being suspicious of the medical establishment is not a sign of paranoia. So what can well-meaning pediatricians do in this context to have credibility with “anti-vaxxers”? I think we start by listening. It turns out when one listens to “anti-vaccine” parents that many of the things doctors think they know about them are not true. There are many varieties of “anti-vaxxers.” Some accept vaccination in general, but want fewer total vaccines or a more spaced out schedule. In general they are not categorically against all vaccines. I have taken the time to listen in person to some of the national leaders of the movement, and these are moms who had their children vaccinated. They believe that their children then got sick because of the vaccines. Worried mothers of sick children are who I was trained to listen to. They say they are doing advocacy to protect other children from what happened to theirs. As a public health scientist, I do not put much weight in personal anecdotes as evidence of causality, but as a pediatrician, I can understand their concern.

For Tyler’s visit to the Mennonites near Penn Yan, he collaborated with Sara Christensen Deputy Director of the Yates County Public Health Department, who gathered questions ahead of time from local parents. The discussion was organized around answering those questions first. Then, the floor was opened for other queries and comments from the audience. The panelists did not just come to lecture. Afterwards, parents came up to thank Tyler and his colleagues. Did this one outreach effort succeed in correcting everyone’s misconceptions about “anti-vaxxers” as well as those about vaccines? Not likely. Did it succeed in building trust that both sides want what’s best for children? I think so.

References:

- Strategies intended to address vaccine hesitancy: Review of published reviews. Eve Dubé

- Lessons Learned From the Opioid Epidemic. Joshua M. Sharfstein, MD, Yngvild Olsen, MD, MPH

- The New York Times, We’re Ignoring the Biggest Cause of the Measles Crisis by Jennifer Lighter Sept 22, 2019

- The New York Times, The Rise of the Anti-Vax Home Schoolers,Ginia Bellafante, September 15, 2019

A Note From The Director June 2019

Drs. Andy Aligne and Andy Sherman in Senegal.

Is There a Right Way To Do & Teach Global Health?

Global aid in general and global health education in particular are areas of controversy, as detailed in books like "Great Escape" by Angus Deaton and "Hoping to Help" by Judith Lasker. Some people argue that people in poor countries would be better off if we just left them alone. I think this is a dangerously wrong-headed idea. While some aid programs are wasteful or even harmful, that doesn't mean that they all are.

Netlife grew out of Dr. Andy Sherman’s experiences as a Peace Corps Volunteer. While living in a small village in Senegal, he got to know children who would go on to die of malaria. This motivated him to found a non-profit to facilitate distribution of insecticide-treated bed nets. These have been shown to have a huge impact on malaria mortality, but nets were very underutilized when he began this work. Through medical school, residency, fellowship, private practice and parenthood, he has kept going back to Senegal to maintain relationships and keep the good work going. Nowadays, net distributions are done routinely by the Senegalese government, but Netlife has continued to look into how things can be improved.

Recently, Netlife conducted a survey that revealed that people needed more nets than World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines recommended. Observations and interviews discovered several reasons for this, including the harsh rural conditions, which caused the nets to wear out faster than predicted. Local people were also sleeping outside regularly at night because of the extreme heat, and that issue was getting worse with global warming. Sleeping outside meant they were unprotected by nets. This was new information that was not in the malaria literature at the time. For a previous project, Netlife sponsored a contest to come up with a practical solution for hanging up mosquito nets outside. Winners got prizes like a cow or a goat. One of the winning teams came up with a wire and rubber contraption that can be made with locally available materials and is easily used.

On our 2019 trip, we went back to help distribute hundreds of these kits along with nets for outside use, and we made a video and posters to help teach others how to hang up the nets outdoors. All of this work is done in partnership with local health workers, doctors, nurses, Peace Corps Volunteers, village chiefs, etc. Everything we do is with very low overhead. We visit the villages by bicycle-not air conditioned SUVs- and pay for all of our own travel expenses. The residents and students who come with us get to watch Dr. Sherman demonstrate his mastery of community relationship building and cross-cultural communication.

We will be getting feedback on the impact of our novel outdoor use of nets from the regularly collected malaria statistics. I go on these trips to help with the scientific evaluation of the project but also because they do me a tremendous amount of good. Hearing all the little children in the village come to “give me five” and say hello while I’m trying to find a spot where my phone works (They have cell service now!), helping the team overcome some of the many obstacles inherent in this kind of work, completing long bike rides – all of those are good antidotes to burnout. And then there is the fact that everywhere we went, people thanked us profusely for helping them to fight malaria, which for them is a real and terrible danger. They all know people who have suffered or died from this disease. One municipal official told us his job is to promote economic development but he can’t do that when malaria makes people too sick to work.

Long-lasting insecticide treated nets work to prevent malaria and save lives. We know we are moving the needle in one of the world’s malaria hot spots. And as explained in historian Randall Packard’s brilliant book “The Making of a Tropical Disease” controlling malaria in places like Senegal can be particularly important for “shrinking the map” and perhaps eventually eliminating one of the world’s major killers. Netlife’s approach is community-level, preventive/upstream, evidence-based, locally sustainable with longitudinal relationships and high return on investment with measurable impact.

I believe that there are many right ways to do and teach global health. The Netlife experience is just one of those, but one example is enough to disprove the nihilistic notion that nothing works.

- Andrew Aligne, M.D., M.P.H., Director of the Hoekelman Center

Disclaimer: The views expressed on this page do not reflect those of the University of Rochester Medical Center.