Collaboration Drives Response to COVID

Fellow and Resident Spotlight

Fellow and Resident Spotlight

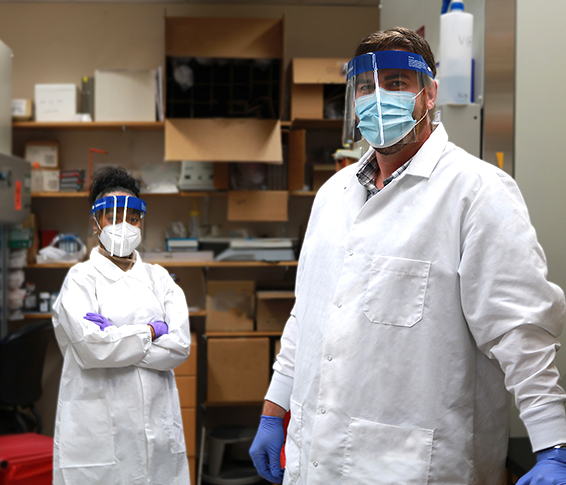

Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, Christopher Anderson, Ph.D., a research fellow in the department of Pediatrics, was studying Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) to understand why this virus causes severe lung infections in some babies.

Across campus, Raven Osborn, Ph.D. candidate in Translational Biomedical Sciences, working for Steve Dewhurst, Ph.D. and Juilee Thakar, Ph.D., in the department of Microbiology and Immunology, was studying the influenza vaccine, using a bioinformatics network approach to understand why vaccine efficacy was so low in older populations as compared to young adults. She had just completed a research proposal and was planning to present it to a committee meeting last March when plans changed.

“I was asked how I could change the focus to COVID,” said Osborn.

As part of this transition to COVID research, both Anderson and Osborn are collaborating to gain a better understanding of how COVID-19 effects the human lungs. For Anderson, this means a marked shift as compared to studying RSV.

“Only young children get severe disease from the RSV virus, but the general population generally does not” he said, “then COVID came along, and we started to see elderly people get severe disease, but younger children all the sudden weren’t, so we set out to understand why.”

Anderson works in the laboratory of Tom Mariani, PhD, and conducts research as part of the LungMAP program lead by Gloria Pryhuber, M.D. The LungMap program studies human lung cells to build an ‘atlas’ of the lung. As a result, Anderson already has the infrastructure in place to transition to studying COVID-infected lungs in both children and adults.

“We start off with a lung, that lung is processed into individual cells, these cells are put into a cell culture flask, and we supply those cells with what they need to grow — which means putting them onto an air-liquid interface where the bottom of the cells have liquid and the top have air — before handing them off the Raven,” said Anderson.

Osborn then infects the cells with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and uses a bioinformatics approach to understand how the virus is evading innate immune pathways and if there’s an age-related component to that evasion. This process — as one can imagine — requires extra safety measures. Osborn works in a Biosafety Level (BSL) 3 laboratory, which is relatively uncommon even among academic medical centers. Getting access to the lab involved a two-month security process for Osborn, and entering the lab requires wearing a Tyvek hazmat suit. Osborn typically harvests infected cells during this lab work, which can take up to 3-4 hours.

After harvesting the SARS-Cov-2-infected cells, Osborn then studies the reaction to the virus. “We want to know at the single cell level what is going on with the genes. Is it changing the cell somehow?” said Osborn, “How does is effect the cells around it? What are the molecular interactions? SARS-CoV-2 is particularly efficient at evading these anti-viral signals, what is making it more efficient at this evasion, and how may that differ in children?”

The opportunities for collaborative work between research labs is a major reason both Osborn and Anderson have settled at URMC long-term. Anderson, who moved to Rochester with his family from Boston, Massachusetts, was drawn to URMC after reading an article on the bioinformatics work done at the institution, and has stayed in Rochester due in part to the strength of translational biomedical science program.

“It emphasizes not just basic science, but science for clinical application and consumer products,” he said. Osborn came from Kansas City, Missouri, to complete a post baccalaureate fellowship. She appreciates the free and flexible approach to research at URMC. “You can collaborate with basically everybody here, and there isn’t a focus on staying in academia,” he said.

While it’s too early to determine results from their project, both Anderson and Osborn are clear: while COVID may have similar characteristics to other, common-cold coronavirus strains, there are no easy answers at this point that explain its effects.

“You can’t ask the same questions that would be asked about the flu, because there are no adults who haven’t seen the flu,” said Anderson, “we are still in the process of determine whether it’s age or the novelty of the virus that causes it to disproportionately affect older people.”